|

| Revisiting an old subject |

I'm quite a recent convert to tonal drawing, starting as late as 2008, prior to that I'd only really used line in my preparatory work. But while studying the SBA diploma course I discovered an interest in tonal drawing. My tutor during the course was fellow SBA member, Julie Small, When I met her in London, I recall she told me that she'd found it an easier medium than watercolour for her busy lifestyle, she produces the most amazing works! I loved graphite immediately and completed many works alongside the course and beyond. Julie was right - it really is the ideal medium for people who find they're time or space constrained and doesn't require the same physical space, storage or long periods of concentration demanded by watercolour ( no colour testing!). I've found it perfect when moving around ...a few pencils, a rubber and paper are all the essentials needed.

I use Faber Castell 9000 pencils - for me they're the smoothest and most consistent pencils, also a mechanical pencil occasionally with 0.3 lead for very fine work at edges, such as on the tips of the thistle drawing discussed below. I sharpen pencils to have long leads exposed by using a scalpel or sharp kitchen knife to trim away the wood and taper the lead. I use a nail file to fine tune the point. The long leads last a long time and just need tapering at the end on the nail file as I work.

|

| Sharpen all the pencils before starting a new drawing |

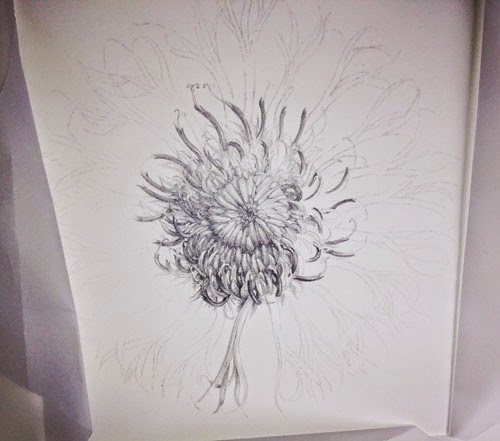

I had been asked in June this year to redraw a Scots Thistle seed head, Onopordum acanthium, at a larger size than the original drawing (x 2.5). The original drawing was completed in 2009, in that drawing I had illustrated two different aspects; one view in profile and from above showing the seeds( below). Having grown the plant in my garden in Scotland, I'd waited patiently for the seed head for the two years it takes to mature and complete it's life-cycle. It was an enormous plant and I really wish I'd photographed the plant in it's full glory.

|

| Original drawing included a view of the seed head from above, showing a Fibonacci sequence |

|

| The poor old thistle! doesn't quite look the same as it did but still useful for detail. |

|

| Early rough drawings - to work out the position of the spikes |

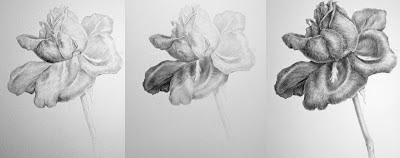

Most of the foundation work was completed with a 2H pencil and the whole drawing used the grades between 2H and 3B ( inclusive)

|

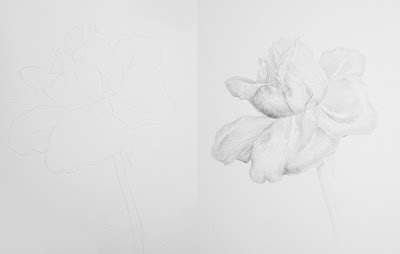

| Beginnings |

| |

| Working between the spines, up close |

|

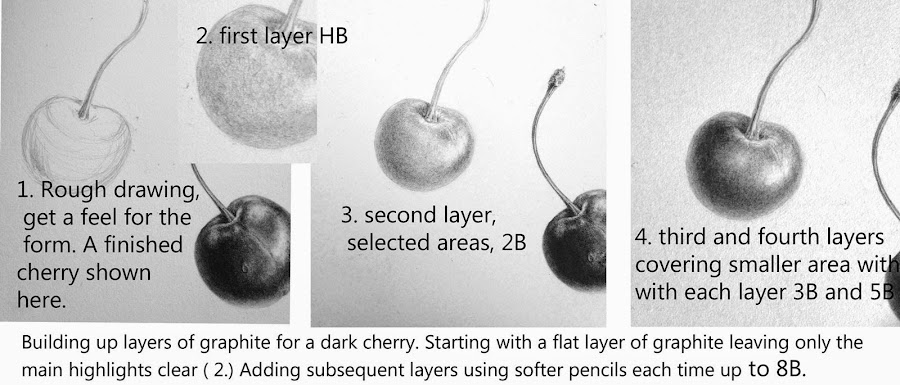

| Building up tone, using increasingly softer grades of pencils |

Below is a video showing some of the process of building up tone on the thistle ( x32 speed).

Below is an example of how graphite was used for an original study of the subject for the final painting of a painting of Primula vulgaris on vellum. You can see the addition of one flower on the upper right of the painted version and the roots. Both were added because I felt that the graphite study composition was slightly empty looking and lacking in interest - hence the additions. Once the 'ground work' was completed in graphite the painting was much easier to complete. Also I prefer dissections in graphite because they don't distract from the main focal point. In this case I decided not to include them in the final colour work but learned a lot on the way! I used the dissections as reference for another painting completed at a later date.

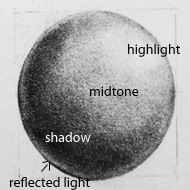

I've been teaching graphite for a couple of years now and strongly believe that it provides the building blocks for colour work but of course it also stands as a medium in its own right. I spent some time overhauling and rewriting the materials over the recent months when I couldn't paint, and try to teach from the very basics; measuring, proportion, perspective, negative space and tonal techniques, as well as incorporating some non-graphite monochrome techniques, which I hope helps students to really see those elusive values ( so using photography and tonal painting too) Students work their way up to a study page and finally a full tonal drawing. I'm also currently introducing a new sections on dissection drawing because it takes us into the heart of the plant and its purpose....reproduction and survival. So yes, a bit of biology in there too so that I don't lose touch.

Fortunately life is now settling down again and I'm hoping to complete some of the projects that I'd listed in my new year blog at the start of the year.... but I know I can always rely on graphite to keep me focused when all around is chaotic.