|

| Details from leaves painted during week one. |

I love leaves! and it's the love of the subject drives the painter on to try harder to do better - and to never give up. There are so many leaves too choose from, many are challenging with incredible diversity and detail, there's more than enough to keep a painter occupied for a lifetime. As Lucien Freud said ' it's what Yeats called the fascination with what's difficult. I'm only trying to do what I can't do.'

I hope to carry on with this challenge for a while and to be a better artist but being fickle, I can always swap to a different subject should he mood change.... for now leaves are good. Here's the sum total of my efforts with some information on the process.

|

|

| Green Photinia, leaf no. 1 This is a leaf with a deeply indented 'V' shaped profile - i.e. it indents at the mid rib. The light is coming from the right hand side. Yet note how the right side of the mid rib is in shade, so although the leaf catches the light near the outer margin, as it nears the mid rib it indents away from the light. Conversely, where to leaf bends upwards, on the left of the mid rib, the light catches the smooth surface, creating a distinct difference between the left and right side of the mid rib. It's at its darkest where the far left curls away from the light This left to right difference is a key feature of lighting that shows the 'V' shaped profile. |

Do try this at Home

If you are thinking of trying some leaves, don't worry too much about the time constraint or perfection but do try to finish a small work in one day. For me, the objective is to capture the overall 'character' of a leaf; its shape, form, colour and surface texture. It's not so much about tiny details or photorealism but more about the 'feel' of the subject. Start to improve your observation and understanding of leaf shapes and surfaces within a very short space of time your drawing and painting will improve too. See previous posts by searching for the 30 day leaf challenge, which I completed several years ago.

|

| Finished leaf |

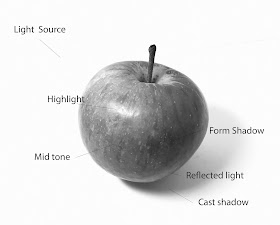

Can you see the Light: Technical stuff

As a tutor one of the most common problems the I see in leaves is a lack of form, flat looking leaves result from poor or diffused light - poor light kills a leaf stone dead because everything is painted using mid tones. To bring a leaf alive you need light and shade (i.e. a range of tonal values). If you're a beginner, the best way of resolving 'flat leaf' problems is to enhance that light, exaggerate it in true Chiaroscuro Rembrandt fashion but use modern technology by using a fixed light source from a lamp. This doesn't have to cost a fortune, any angle poise lamp with a swivel head will do, then fit with a photographers bulb E27 screw fit, use 5,500k (Kelvins) which is the nearest to natural 'white' daylight and easy are to buy on Amazon or from photography suppliers, don't look in art suppliers for bulbs, many claim to be daylight but are not. Bulbs over 6000k give yellow light and bulbs under 5000K are blue, so will not give accurate colour. You also need the correct CRI, (colour render index) of 90 or above or as near as you can get. Bulbs with CRI over 90 are more difficult to find and you may have to settle for 80 but the higher the CRI the better the true colour. Light from the upper front left if right handed and the right if left handed, although I tend to light from the side the I think looks best for the subject. Pin your leaf to a piece of white foam board and light from your chosen side, move the lamp around to create good contrast. Try painting in black paint or ink first to avoid confusion between colour and tone.

Look at Ruskin's tonal studies for inspiration, it's all about light and shade, note the dramatic difference either side of the mid-rib. Study the masters!

|

| © University of Oxford - Ashmolean Museum From Ruskin's Elements of Drawing, watercolour and bodycolour over graphite click for reference |

Observe and Draw

Make sure you get the leaf drawing correct, double check the typical features of a leaf and look at a few different ones if you're aiming for botanical accuracy, alternatively, you can just go with whatever takes your fancy, some leaves are more interesting than others, so choose wisely. Make quick notes on leaf shape, margin, tip and base, venation pattern and surface texture, measure height and width and note the widest point too as this can be a key feature, if you measure you can't go wrong. At this point , ask yourself what are you trying to portray, is it shiny, mat, puckered or hairy surface etc. Being accurate in your portrayal of any subject is important so never short cut the observation and drawing. Keep pencil lines minimal and light. I use a H grade for drawing.

|

| Limited Palette with sufficient range of blues, reds and yellows does not impose any limitation on what is possible. I've been working with this palette for years. |

Painting Materials - what you need and what you probably don't need

My palette is limited to primaries, this is the best way of working for me, it keeps it simple and I can shift a mix to warmer and cooler versions of the basic hue - look carefully and you will see how light affects colour across the surface of the leaf, this is where using three primaries really works because that colour shift is made so much easier by adjusting the ratio of colours in the mix. There's no need to have the whole colour range from every supplier. Heres my basic materials list for paints and everything else. With regard to paper, I'm not discussing Fabriano any more, yes there's a new one but I moved on anyway. I've tried a few different papers in the last few years, it takes time to get to know them, I mostly used Saunders Waterford HP high white 300gsm - it's a decent enough paper which takes a bit of effort with the edges but is tough and the colour is good. Botanical artists tend to prefer hard gelatine sized papers, starch sizing is generally a little too soft. I'm a fairly dry painter and careful washes is the best approach and if you work dry, so you never need heavier paper than 300gsm, it's pointless spending money on the heavy papers if you don't need them and often they are not so smooth as the lighter weights ( Arches being a prime example, the 300 and 600 gsm versions are like two different papers). I sometimes paint on Schoellershammer 4G which is super smooth and lighter in weight but because work dry there is no cockling, sadly this is another paper that appears to be discontinued. Brushes, usually size 2 and 4 series 7 miniatures and a size 1 short flat synthetic there are lots available. I did switch brushes for some of the leaves, which were painted with synthetic Betty Hayways brushes, I used the larger sizes 4 and 7 which worked well, point and belly are good but the small sizes are less so and as with most synthetics the tip goes quite quickly but I found I could use the large sizes for everything, even the dry brush. Use an elevated drawing board so that you save your neck and can see what you are doing and finally, use a magnifier! x2 is sufficient, more magnification isn't helpful as you can only see a tiny area also excessive magnification hurst your eyes.

Starting to Paint

After making a very simple line drawing with as little graphite as possible on the paper. I begin with underlying colour, in green leaves this is usually blue, a high light value blue, such as Cobalt, Cerulean or Manganese. In red and brown leaves, yellow and violet can be involved too, so this can require an underlying blended wash of several colours. You will see this in the various step-by-step images.

|

| Finished Camellia |

Work up the whole leaf, keeping the light with selective application of colour

I can't stress how important it is to work up the whole leaf in stages, this is how you capture the light and shade to create a dynamic painting. If you try to finish little parts at a time, the end result can be quite flat and lacklustre, although it can start off ok, it often ends up disappointing ( I'm sure we all know that feeling). I work up all of my paintings in this way and the more complex the painting, the more important it is to attack as a whole. After the underlying wash I add colour selectively working on one leaf blade at a time. I dampen and add colour where needed, which avoids adding too much water and painting over the highlights, conversely, adding too much water in all-over washes flattens, loses highlights and creates hard untidy edges.

|

| No. 4 Finished...sort of |

Depth and Detail

Once I'm satisfied that I've added enough colour using selective washes, which is usually only 2 layers after the underlying wash, I start to use different dry brush techniques. Sometimes I use a 'scumbling' technique for texture, I use dry on damp for smooth deep colour with creamy paint to 'model' the surface, for creating rich colour and shadows. I also use a 'sweeping motion' for long leaves and a 'drawing' technique on damp and dry for detail and finally a 'polishing' circular motion which is the driest, and creates the shine. I use much the same techniques on vellum but with fewer washes.

|

| Leaf no. 5 Holly finished |

What you may have noticed is that the order is much the same in all of these leaves, there is some 'back and forth' in terms of approach but its broadly the same 1. underlying wash, 2. Selective colour layers into wet (2 or 3 layers) 3. Depth and Detail with dry brush on damp 4. Finishing touches and review.

|

| Process of the front in stages and the latter stages of the back. |

There wasn't much left in the garden by the time I reached leaf no 7. but I was determined to finish this. I chose an ageing rose leaf, which was pretty much about to drop all its leaflets except the green one, which was clinging on for life. This explains the missing leaflet on the left hand side. An interesting one to paint because I used 3 different underlying colours, blue, violet and yellow. I decided to paint this one on Schollershammer 4G paper, which is great for crisp edges and most like the surface of vellum - but use too much water and it will look like the mountains it will cockle so much. It's a great surface if you're in training for vellum and want to work dry. Alas, its a shame that it doesn't seem to be available any more as its my favourite paper for drawing too. Such is life.

Thats all folks! .......until next year.

Wishing you a great New Year with much painting in 2020